Living and Dying on the streets of Brazil

Living and Dying on the streets of Brazil

Peter Machen talks to director Fernando Meirelles about his extraordinary action film City of God

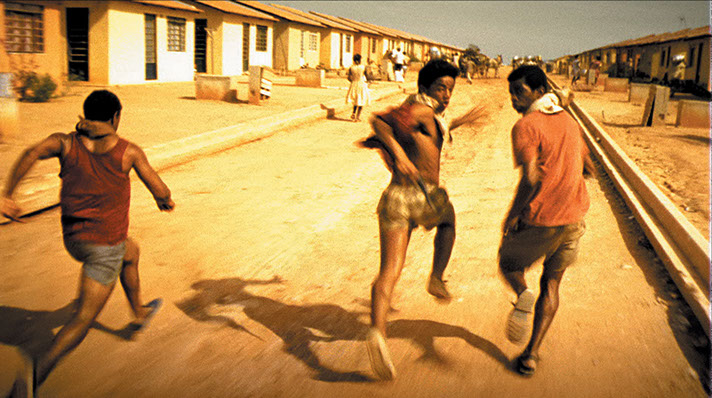

The multi-award winning film City of God chronicles the lives of Brazilian street children living in a sprawling housing settlement on the outskirts of Rio, named the City of God by its residents. It is an extraordinary film, an instant classic that stretches the limits of cinema while at all times being just as engaging as say Pulp Fiction or Terminator 2. Based on the 600-page novel of the same name by Paulo Lins, the book follows the lives of more than 250 protagonists until each life is snuffed, a victim of the drug-based gang warfare that constitutes the pulse of a sub-city that has been forgotten by the society that created it. But City of God doesn’t explore the social construction or political nature of the settlement of street children. It simply plays out the lives of the characters until their inevitable end, the devaluation and desecration of human life a vastly ample critique of whatever society created it. I spoke to director Fernando Meirelles about the process of making this incredible film.

Peter Machen: Apparently you weren’t that interested in the project initially, but by the time you were halfway through the book, you were convinced that you wanted to make a film of it?

Fernando Meirelles: Yes, but I had no idea how to do a movie about it. I finished the book and I was really amazed by it. The images and the characters kept coming back and so I had to do something. But I had no idea what. So I first bought the rights and called my friend Brulio, who was a writer, and I said, "read this and tell me how can I take a film from this thing". It’s a huge book with more than 250 characters. And then we worked for about two years on it.

PM: Does the super-realism of the film come from the book?

FM: Actually the book is very episodic. There’s no structure. There’s no storyline. It just presents a character and follows this guy and then presents this guy dying. And then he introduces another one and then he dies. And that’s how he goes through more than 600 pages. It's really a lot of characters and a lot of situations. But all of the stories are real stories that Paulo Lins heard. For eight years he was writing this book, living in the City of God. So every day he was reading newspapers and talking to people and getting all those stories. That’s how he wrote the book. It’s very realistic because it’s all based on true stories. And the way he writes is really poetic. Sometimes it becomes almost poetry – that’s also what gets you.

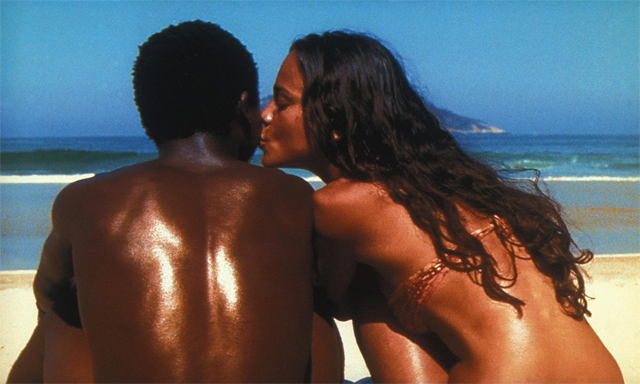

PM: And is the City of God in reality as racially mixed as it is in the film?

FM: Yeah, yeah.

PM: Brazilian society is like that?

FM: Yeah. Like you can see in the poster, there’s a white girl with a black boy. This is very usual. Nobody cares. I think there’s a social apartheid, but there’s no racial separation. It’s really mixed.

PM: That’s what’s starting to happen here. The racial divisions are disappearing and becoming economic ones. Brazil and South Africa have very similar economies in many ways. They both have the biggest wealth discrepancies in the world.

FM: I know. I know. And I can tell by walking around here. Going out in these streets you have these incredible, beautiful mansions and then you see so many squatter camps. It’s like Brazil.

PM: But what there isn’t in the film are glances at the super rich. There’s no contrast between the incredible poverty on the one hand and then the super wealthy on the other.

FM: I know. Because the film is about City of God and it’s a story told by somebody from City of God. And people that live there don’t go to other places, they have only that perspective. He believes in that place and that’s what he sees. That’s his world. And I’ve been criticised by some Brazilian critics – well, I’ve been criticised for so many reasons – but this was one of the reasons. People saying that I was not showing the whole society and I was not explaining how and why this situation exists and all that. And my point is that what I like about the film – and this was my starting point with the film – is that this is a story that a 15-year-old boy is telling to us. So he doesn’t know about government, or things like that. He just sees what he sees. He’s telling what he sees.

PM: And I do think that film is very powerful for having done that.

FM: And having just this point of view. I don’t need to try to explain. In Brazil, a lot of films and books involve the middle class talking about and trying to explain social problems. I see this a lot. And the original thing about this film is not having to explain. It’s not my opinion. You don’t know what I think.

PM: There’s no lecturing in the film.

FM: Yeah. That’s why I decided to work with no professionals. So I could use the boys’ expertise and not my own. I really tried to stay out of the film as much as I could.

PM: Are you a fan of Larry Clarke (the director of the controversial film Kids).

FM: Yeah, yeah. I like Kids very much. Kids is really an amazing film

PM: Your film reminded me a lot of Kids in a way. Although they’re completely different films.

FM: No, no. I think they have a lot in common. Using non-professional actors, the way he prepared the actors – and letting the boys do whatever they want to do. The camera’s like a documentary camera. He creates a happening and the camera goes there and tries to show as much as it can – like a documentary. And that’s also how I’ve done it.

PM: You talk elsewhere about the idea of the non-photographs, which I also associate quite strongly with Clark as a photographer [Clark is also a celebrated art photographer].

FM: Well, this is really what I’m talking about. When you do a film you get a perfect frame and a perfect composition. Non-photography means you just do what ever you do and I’ll try to do my best. I’m not worried if the light or the shade is going to be this way or that way, or whatever, just go.

PM: Now that you’ve made the film, do you think that there’s hope for the City of God and for all the other cities of God around the planet?

FM: I do. But I really think that it will take a long time, 25 years at least. Because even if we begin to do something now, there’s a generation, boys of 11, 12, who are already involved in crime and who use guns. And it is very expensive to convince one of those boys to give back his gun and go to school. It’s really very expensive. It’s more possible to convince 8 or 9-year-old boys to avoid getting into crime. It’s much, much easier than getting a 14-year-old boy out. And I think the only way to solve this problem is investing in social inclusion, bringing these people into our society. Because every time I hear governors and everybody talking about fighting against violence, there are always people saying how they’re going to invest in repression. We’re buying four new helicopters and we’re going to buy 35 new cars and the police are buying guns and all kinds of thing. But instead of investing in repression they should do the opposite. You’ve got to bring those marginalised people in. And provide schools, and sports, and culture.

© PETER MACHEN 2017