Waiting with

Waiting with

Winnie Mandela

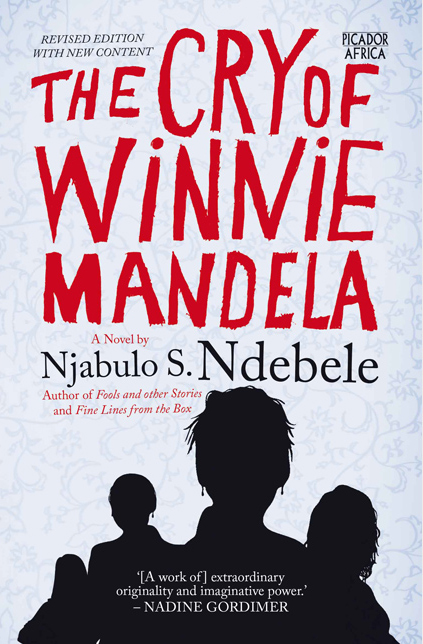

Njabulo Ndebele is Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town and author of several fiction and non-fiction books, including the classic collection of short stories, Fools and Other Stories, and Rediscovery of the Ordinary, a collection of critical essays. Ndebele was in Durban for the Time of the Writer festival. I spoke to him about his latest novel The Cry of Winnie Mandela

The moment I heard about The Cry of Winnie Mandela, I thought it was a brilliant idea. Incorporating Winnie Mandela, so ungraspable in the realm of normal reportage, into the safety of fiction is a beautiful literary conceit. But the book is only nominally about the former Mrs Mandela, and more centrally about black African women who wait for their men, of whom Winnie Mandela is only one of many.

Ndebele details the lives of four African women, Deliswe Síkhosana, Patience Letlala, Manette Mofolo and Marara Joyce Baloyi. Four women who have ended up single and alone, after having spent most of their lives waiting for their men. Men who have left the homestead as a result of exile, studying, migrant labour, poverty and, sometimes, for no apparent reason at all.

These four women meet at regular ibandlas, or meetings, where they share in the solidarity of having been left. In the course of their conversations, the subject of Winnie Mandela comes up. They talk about Winnie – Winifred Nomzamo Zanyiwe Mandela – who waited so publicly and for so long for a man whose bed she did not end up sharing. And, as they talk, they come up with the idea of each entering into a conversation with her at their ibandlas.

Through the human ether, Mandela somehow hears the voices of the four women, and, after they have all told their tales, she tells hers. Here Ndebele blurs fact and fiction, as Mandela recounts her pain and her love. And behind Mandela, behind the four women, lurks the shadow of Penelope, the archetypal women-who-waited, Penelope who waited 13 years for her husband Odysseus to return, only for him to destroy the life to which he was returning. And then there is Quesalid, the Indian shaman who set out to unmask the shamans and ended up becoming one...

I spoke to Ndebele about this remarkable book and about his views on Africa, women and the future.

Peter Machen: The story of Penelope is thousands of years old, and yet women all over the world and particularly in Africa are still waiting for their men, and also for equality. Do you think the time will come when women get a fair deal?

Njabulo Ndebele: I think that this is suggested at the end of the novel, when Penelope appears as a backpacker and says she's been traveling for a thousand years, taking the message to women all over the world, wherever, in her view, there has been a significant increase in the freedom of women. This has a lot to do with what she calls "the growth of the world's consciousness", and so it is an unfolding human process. And I think that we should be able to judge the evolution of human society for the better to the extent that freedoms of people, women, children, and so on, are increasing all the time. So it is an unfolding process. And I hope the world gets better the more these freedoms increase.

PM: That is also kind of my personal spiritual belief, this growth of consciousness. That is also a very personal thing for you?

NN: Yes indeed. I once did an essay – I don't know if you saw the article, I think it was in the Sunday Times. This particular article was on the gay question. And there was this hullabaloo over a gay bishop in the United States. And the angle of my article was precisely that the gay issue is also an instance of the growth of consciousness. There are so many other things about the world – the way we solve the problems of Iraq, for example, has to do with that. I think the United States' governance systems have gone as far as they can in promoting human freedom and they cannot go beyond themselves. What we need is a different vision of world governance which does not depend on one big country. And ja, that's what it is really.

PM: Back to The Cry of Winnie Mandela. Do you have any personal relationship with Winnie?

NN: No, I don't.

PM: Do you know if she has read the book?

NN: I have no idea. It's a challenge for South African journalists. I am surprised that no one has asked her.

PM: Ja, I'd love to sit down with her and talk about it. Do you think there is still life in Winnie Mandela in terms of party politics, as opposed to extra-party politics?

NN: I'm afraid I don't know. I think that the book does not deal with that. The novel is exploring a different dimension of experience and not essentially a political one.

PM: But it does show the place where the two overlap?

NN: Yeah, I'm sure it does. I would suspect that, for Winnie, the two planes of reality – as a human being on the one hand, and as political leader on the other hand – exist in a state of tension. And part of that tension means that you can never fully say that you have summed her up. There is no telling what next she might do, that either elevates her, or disappoints people. So she remains an interesting person that we are highly unlikely to lose interest in.

PM: Would I be correct in surmising from the book that you hold a good deal of abstracted affection for Winnie?

NN: I think I have a sympathetic approach to her. And in the same way that I have a great deal of affection for the other fictional characters in the book, I have affection for the fictional Winnie as well.

PM: That's very interesting, because you are also quite blunt regarding her, the fictional Winnie. Was this in any way a difficult book to write, in terms of that?

NN: Ja, there were parts that were not easy to write. But, you know, the most important thing about the book in response to that question is that it set out to be a work of art. It does not set out to be a feminist story, nor does it set out to be a political assessment of Winnie. This does not mean that feminism and politics and power are not central themes of the book – they're definitely there. But I think the book sets out to be a work of art, and so, to the extent to which I had to deal with difficulty, it was basically to solve artistic problems.

PM: The book is also a fictional historical text, if I can call it that. And lying at the heart of Winnie Mandela, both the fictional one and the real one are a lot of unpalatable truths. Do you think that the South African public can cope with these untold truths?

NN: I think, more than ever, that our society can cope with them. Because we're still going through the stage in our democracy of putting issues on the table. We're probably going to be doing that for the next two decades. It's a maturation process. We can't mature without putting these things on the table. And we've been doing so for the last 10 years. These things test our democratic resolve, they test our institutions of democracy to the extent that they can cope with them, they test the constitutional court, they test our universities, our churches and all that. I think it's wonderful. I think our society can handle these things.

Now, another thing, in relation to the very last question before this one, is that it would have been difficult to talk about Winnie alone, without the other women. In a sense they prepare the ground for Winnie's own story. And she's very conscious of that in the book when she starts. She can see from the testimonies of the other women that she can open herself up because they have opened themselves up to scrutiny. She feels confident that an attempt is being made to understand, not to judge. And I think the Truth and Reconciliation committee did set the stage for all sorts of issues to be put on the table and not necessarily for judgment. And that deepens the ethical imperative.

PM: I remember very vividly that famous day when Winnie appeared before the TRC with Tutu egging her on. Do you think back then that it was possible for Winnie to tell the complete truth to the TRC.

NN: I don't think it was possible. I don't think she could open herself up completely because she was still distrustful of the reconciliation process herself. The fictional Winnie says in the book that "reconciliation demands my extinction" and so she's inherently suspicious. And still, there's a side of her that wants a total solution, the total transfer of power, the eradication of poverty and so on. And so, to the extent that we went for a negotiated settlement, she remains one part of the dialectical poem that reminds us that we didn't have a complete revolution. And to that extent, voices such as hers are a reminder of unfinished business. So I don't see that she would then just have gone out there, and confessed like everybody else.

PM: One final question. As Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town, you are in a position of extreme privilege. Do you ever feel a conflict between your position and the position of the women in the book?

NN: It's an interesting question. I seldom experience my position as a position of privilege, it's a position of constant hard work [laughs]. I seldom think of the job in that way. I think that there is a constant conflict between my desire to be an artist and my responsibilities towards being a manager and an administrator. There are different kinds of demands.

And I would suspect that the artist in me always ensures that I do my job in a compassionate and imaginative way. The possibilities of exercising the imagination are all over the world, wherever you are. So I'm more readily, more easily, able to put myself in the shoes of many people in situations of dire stress. It is not difficult for me, having grown up in a township in a relatively middle class environment with working class culture all over. I have grown up with the flexibility to move in and out of all kinds of situations and be relatively comfortable in them. Which I guess explains why I never really thought of my job as a privileged one.

© PETER MACHEN 2017