Dream of Life

Dream of Life

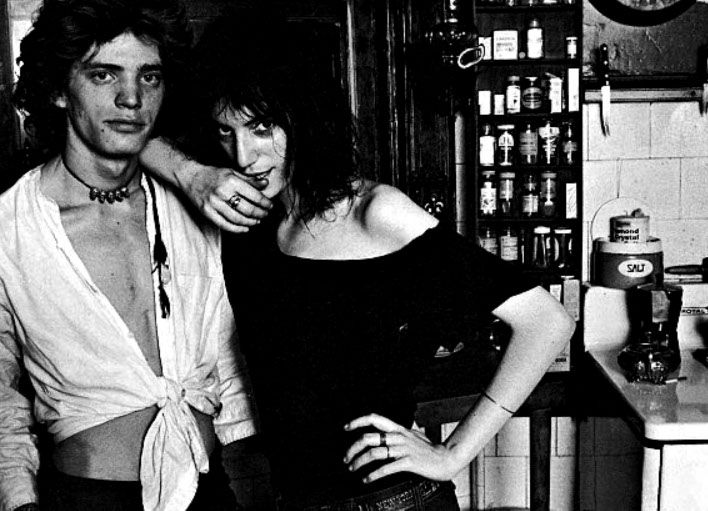

In a highly personal interview, Peter Machen spoke to Patti Smith about being the high priestess of counterculture.

When I speak to Patti Smith at 10.30 on a Tuesday night, she has just arrived in the mountains of Norway after a day of travelling which involved two plane trips and a long car journey. She is clearly tired, and when I begin thanking her effusively for the interview, she asks me politely to get on with it and do what we can. But I think she quickly realises that my adulation is not blind, false or obsequious, but a result of being genuinely affected by her work, that I really do have things to ask her beyond what her favourite colour is, and she soon warms to the conversation.

Peter Machen: I’m not going to ask you what it feels like to be a rock and roll star but I am going to ask you this: How do you feel being the friend and companion to generations that follow you in the same way that Rimbaud and Whitman and Burroughs and Blake were friends and companions to you?

Patti Smith: Oh… (laughs)… I couldn’t say that. I mean if you’re saying that…

PM: I am saying that!

PS: Well, I mean, it’s quite an honour. I mean, what could one say? You know, if you can, if you can um…you know all of these people have certainly given to me, and if I can give to others that’s a great thing. But it’s not something that an artist should think about himself, do you know what I mean?

PM: Yeah, I do…

PS: It’s one of the (laughs) it’s a…it’s a very nice thing to think about, but you know, I mean...I...All I can say is it’s a beautiful thought.

PM: And you made really incredibly beautiful music to break through, to get to me, you know, as a nineteen-year old, twenty years later, on a different side of the world. So, I mean, that just amazes me. And I…you know...I…thank you is all I can say.

PS: Well, thanks. I mean the thing is that as you grow through life, you know, the pursuit of art and the pursuit of new ideas, all these things keeps your mind elastic, and so it’s …you know I am the age that I am but I still look at things always with new eyes. And hopefully if people can look at my work in the same way, that’s a really wonderful thing.

PM: And do you ever struggle to keep those eyes new? Are there ever moments when you feel disillusioned, when you like get irritated with the world, have just had enough? You know what I mean?

PS: Well, I get irritated with the world. I get irritated with politicians, I get very irritated with governments and with corporations but, I mean in terms of…you know...I ..Imagination, you know, we’re given an imagination. And my imagination is always fertile. I’m either thinking of my own things, or constantly engaged by the things that other people do.

And it’s so great, because we have such a great depth of human history in all of the arts, whether it’s opera or mathematics or painting or classical music or jazz. There’s so many things to study, new books to read, and certainly always ways to transform old ideas and to come up with new ones. So, I have to say that I’m never bored. I mean I might sometimes feel discouraged or frustrated, but never bored.

PM: One of the things that resonates with me is the fact that you’ve said on several occasions that you have felt alien to the human race, that you came from somewhere else.

PS: I hope (laughs).

PM: I don’t want to overstress my connection to you. I’m just another person on the other side of the world. But you know, when I was a kid growing up, I really felt that quite profoundly. And I just wonder why we think this, you know, is it part of a social response or…?

PS: Alright. I think that some of us…I think some of us just do. You know the feeling that you’re speaking about that you feel is a real feeling. And I think it’s because some people are more connected with our most ancient past than others. I’m not saying that some are better than others. I’m just saying that some of us channel the most ancient times. And you know, when I was a child, I was certain that I could remember what it was like to live on Venus, I could remember what it was like to live in the American Plains. I could remember…And it’s ancient memory. We all have it. It’s just that some of us access it more than others.

And I think that thing is a special thing but it also makes us feel somewhat alien, somewhat removed from our present. You know, I’ve spent so much of my life just feeling comfortable in the world that I’m in. And one of the ways that I’ve been able to feel that way is just by doing my work, just by – you know, some of the things that make me feel strange – I’ve transformed them into work. Maybe it might be a poem. Maybe it’s a song like Rock and Roll Nigger. That kind of feeling drew me to write a song like Rock and Roll Nigger. Rock and Roll Nigger is all about that exact feeling, outside society, it’s where I wanna be. But it’s also not always where you want to be, it’s just where you are.

PM: But I reckon it’s a good place to be. Clearly for you, it’s a very good place to be. This idea of channeling is one of my questions. Clearly when you write, when you perform, things are coming from an unconscious well. I just want to ask you, as a song writer, as a craftsperson: to what extent do you polish your words after they have sprung from the source? Do you re-arrange them, change them around? How much stays unchanged?

PS: Well, when I improvise, I don’t polish them at all. I mean, like on my albums, there’s a lot of improvisation - on Horses, Birdland – it’s an improvisation. Radio Ethiopia was an improvisation. Radio Baghad. Ghandi. Memento Mori. Almost on every album – Wave is an improvisation. I don’t clean up or edit or polish improvisations. I leave them as they stand - because they represent a moment where we’re struggling to channel something. And it’s not about perfection. It’s about communication.

When I’m writing a poem, when I’m hoping to achieve some kind of perfection, then I’ll spend a lot of time perhaps working and reworking it, which isn’t always the best thing, but it seems to be part of the process. But improvisation is really about achieving communication in some higher realm in the moment. And it’s a very honest way to share your direct creative impulse with the people. If you give people a poem that you’ve rewritten and rewritten and worked on, the original creative impulse is in there, but you’ve also added layers of your own…um…well labours into it. But when you improvise live, the people are seeing the naked creative impulse. So that’s a whole other experience.

PM: Okay. And it is an amazing thing to see…

PS: What do you do? What are you interested in?

PM: Music more than anything, although I have no talent that I have ever accessed. But I write poems, I take photographs, I write for newspapers, I layout art catalogues. I do all kinds of things.

PS: How old are you?

PM: I’m 45.

PS: You seem like you have a very interesting mind, like you’re very uh…um…because those are interesting questions that you asked me. I’m sorry to ask you such personal questions, but I was just curious.

PM: No no. I mean I’m asking you very personal questions…

PS: Yes, but they’re very, very interesting questions. People ask me questions all the times and the questions that you asked me are unique, that’s why I asked you that.

PM: I can’t tell you how much that means to me Patti. I was sitting here and I was scared my questions weren’t good enough. So, yes, I’m incredibly happy that you think that Patti…

PS: [laughs] So ask another one.

PM: I saw you in 1999. I think it was the first date of a European tour – at the Forum [in London]. And it was amazing. I really…I mean I will keep that memory for ever. And I even gave you a hug afterwards actually!

PS: Well, thank you, I probably needed it. Because I was just beginning again. I was probably a bit nervous. But thank you.

PM: You took it with such grace. And what struck me, both on stage, and just standing next to you for like thirty seconds, was that there was no barrier. And, you know, rock musicians often do construct that barrier. And I just want to know if, when you started out, you ever thought that you were above the audience, if you ever had that kind of patina of arrogance.

PS: No. I had a lot of arrogance but not that kind of arrogance, because I was really very conscious of being one of the people. I mean I was also conscious of the fact that I was…I believed I had special gifts. I mean, I feel like an artist. I’ve always felt like, you know, God has given me special gifts. So I understand my own worth. But in terms of being a performer, especially in the context of rock and roll, I…you know I had no special talent. I was not a musician. I could sing a little…It was all bravado, and I really felt that I was exactly that, one of the people.

And one of my goals, and one of my missions - within rock and roll - was to break that barrier, that idea of, you know, of the big rock stars that had a lot of money and attitude and felt like they were, you know, above everybody. Because I believed that rock and roll was the true grass roots art.

You know, everybody can’t paint or write a poem or achieve, you know, certain intellectual success. But rock and roll is a very simple art form. It’s based on a few chords, on a sense of revolution, on a sense of sexuality. It opens its doors to anyone, and I have always felt that, onstage or off-stage, I’m just the same person. I don’t have a persona.

Of course, when you’re younger, you want to be cool, and you know, I could have been a real asshole. But I wasn’t. It’s just that I had a lot of energy and bravado. It wasn’t because I thought that I was better than anyone else. It was just because I had a lot of …you know…arrogant energy.

But in terms of, you know, what you said…I mean…my son, for instance. My son is a great guitarist and he plays with me. And sometimes we’re on stage, and we just start…you know…in the middle of a solo, he might come up and we might start talking to each other. My son has no stage persona. He doesn’t come onstage and turn into Gene Simmons. He’s himself.

Just a minute. Hello. Yeah. Yeah. Just a moment. Yeah, oh, I’m…

Everybody’s looking for me.

PM: And I’ve got you. I’m so lucky.

PS: [laughs] But yeah, you know…one has to be self-protective because people have to have their privacy. I completely believe in the right of privacy of artists. I don’t believe that artists are kings. I just believe that they have special skills, or special gifts, but it doesn’t make them better than anybody else.

PM: Yeah. I mean I do heartily believe that nobody is more important than anybody else on this planet.

PS: Well, also, it’s the way that we conduct our operation. You know our crew is respected, and there’s a strong equality within our operation. And I look to my crew with the same regard as guitarists or anyone. Because they’re the one’s who do the hard labour. Rock and roll is a collaborative process and you have to have respect for everybody involved.

PM: Something that I think is quite remarkable is that you’ve been successfully able to acknowledge the cultural and artistic importance of Horses but you’ve also managed to continue to make new work that exists on its own terms. Did Horses ever feel like it was an albatross around your neck. Was it ever difficult to maintain that balance?

PS: No not at all [laughs]. No, I don’t feel like that at all. I mean, I’m proud of the record. I still sing the songs on it. You know, I’m always working on new things, and always working on new photographs or new poems or new songs. But the work that I do for the people, which is on my records, to me those records belong to the people. And if they want to hear Because the Night for the one thousandth time, I’m happy to sing it. And to sing Gloria, to sing People [Have the Power], to try and keep a relationship with these songs, and, you know, remember what compelled me to write them.

And uh, you know, Horses is not great technically. I didn’t know anything about singing when I did Horses and, um, it has its flaws. But I also know that I did it with everything that I knew how. Everything that I knew about poetry, all the things that I believed in, I tried to put into that record. And so, you know, that was a long time ago, and I’ve certainly evolved since then. But I can look at it and say ‘I did my best that I could’. I don’t look at it and think ‘oh, I compromised’ or that I wasn’t really paying attention or that I was too fucked up to do this record. I put everything I knew into it.

And you know Horses was really…I really put out Horses for people who did feel alienated. Because I felt that I really understood people that felt alienated for whatever reason – because of their sexuality, because they were just wierdos, because they weren’t accepted by their peers or their parents or, you know, for whatever reason. And I think that it stands for that, and it’s amazing how many people through the years, and still now, tell me that the record has meant something to them. And that’s something, you know, that makes me feel very proud.

PM: And it is incredible. I’ve been listening to the album solidly, and also to your other records and your newer stuff. It’s elemental. I’m burbling now but um…

PS: That’s okay. That’s okay.

PM: You have experienced much loss in your life. Anyone who knows a little bit about your life knows that. And some amazing people have left you - and they have also clearly not left you. But already on Horses, on that first record, there is this profound and also almost transcendent sense of loss in your protagonists. And…and…

PS: Well, I think it’s because…yeah, go ahead.

PM: Well, I was going to ask you why, at that point in your life, you were ready to express such vulnerability and such strength?

PS: I think it’s because when I did Horses, my generation – I mean I was about 26 years old – and since I was a young girl...you know, I was a teenager when President Kennedy was shot. I was working for Robert Kennedy when he was assassinated. Martin Luther King was assassinated, and then other people that, you know, we put such faith in. In those days, we put a lot of faith in our rock and roll stars. There wasn’t so much diversion as there is now. And people really looked to the musicians. They kept us informed musically and politically, and they kept us in touch with the cultural revolutions.

And you know Jimi Hendrix died, and Janice Joplin and Jim Morrison. And this was a terrible blow to my generation – to lose Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King and Janice Joplin and Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison in the space of two years. A couple of years, all of them. And Brian Jones. It was just…you know...so many hopes and dreams – that a certain type of unification through, you know, love and no matter how naïve it sounds, so many people believed in that. And then losing a lot of friends in the Vietnam War – I lost a lot of classmates. So by the time I was 25, it seemed like the whole idea was dying.

And that’s one of the reason I did a record. I mean, like I said, I wasn’t a musician. Still, some times it amazes me that I actually even did a record. Because it never was one of my goals. I wanted to be a painter or a poet, but it just organically evolved that way.

And it was my way to summon certain people. Because Elegie was written for Jimi Hendrix. The whole Land-Elegie piece at the end was written for him. Break it up was written for Jim Morrisson. Birdland was written for Wilhelm Reich. It was a mirror into the culture of our time, or my particular time.

PM: That particular time – the late sixties and early seventies – is often described in stories about you and, in general, as a freer state. Is that true? Were the ’70s really freer, more enabling times than the 21st century? Do we have so much less freedom now? I mean, it feels like it from my perspective, but I don’t know how much of that is mythology.

PS: I don’t think it was so much that there was freedom. It was that people were fighting for it and gaining it. It not that it just was sitting there. You know, homosexuals were fighting for freedom to be themselves, and freedom not to hide and be looked down upon. The women’s movement was very strong. The civil rights movement was strong. We were trying to end the Vietnam War.

You know, I wasn’t really part of the drug culture of the late sixties, so I couldn’t really tell you so much about that, because, you know, I was living a different kind of life. I was going to school, and I was working in factories, working my way through school. I worked all the time, and I didn’t have the lifestyle. I wasn’t a hippy, you know. I was a person who, you know, studied art, studied poetry. I was culturally intelligent but I wasn’t really part of my culture. I was more of a seventies person, even though I’m old enough to have been a sixties person. Because of the responsibilities I had in the ’60s, I wasn’t really part of the drug culture.

Also, I wasn’t attracted to the drug culture. So I think it wasn’t so much about the early seventies, not so much about freedom. It was about acquiring freedom. And that struggle produced a lot of great art. Once you have freedom, sometimes people forget how hard it is to get it, and they don’t use it wisely.

PM: Yeah. I feel that strongly that we’re not always using our freedoms in the correct way, and also recognising their value.

PS: We’re in a very material time in our society where people imagine that freedom means they have a lot of things. You know, they might have the best iPhone, or they have the best computer, but you know, it’s not really freedom. It’s just a different kind of slavery. You’re a slave to your credit cards or to the interest or whatever else, or to your stuff.

And I think that we’re going to have to go through a re-examining process and try to get back to the place where – not where people were in the 60s, because I don’t believe in going back in time – but to at least examine ourselves and think ‘well, what makes me an interesting person’, ‘what makes me a good person?’

You know, right now, we’re in this weird place where people are very materialistic. We’re in a place where people are so concerned with their appearance that young people are getting plastic surgery. And it’s just rampant…almost a disease. And really, the thing that will keep people young and beautiful is really working on their inner self. And no matter how corny it sounds, it’s true.

PM: Fully!

PS: You know, if you eat well, if you exercise, if you’re positive, it doesn’t mean you can’t have fun, it doesn’t mean you have to be square. But if you have a clean house inside, you’re going to be a beautiful person anyway.

PM: Aah, that’s great Patti. And it leads very beautifully to my last question which is really just about that. Do you think that, collectively, w

I mean… the way things are, they’re a lot worse than they were in the early seventies. It’s an atmosphere that I recognise. It’s the atmosphere that made me do Horses. Because I looked around and thought “What the hell’s going on?”, you know, “what’s wrong with people?”. They’re forgetting who they are. And um, in some ways, we’re forgetting who we are. And so we have to you know…New generations will make records or write poems or get involved in politics. There are always good people that are ready to make change. And you know, I feel discouraged sometimes, especially in my country – my country is very discouraging. But on the other hand, I just, I don’t know what it is…but…I mean life is beautiful.

PM: It is.

PS: We have a relatively short life span. But of all the things that we can get, you know, all the material things, life is the best thing that we have. And if you’re living and you’re breathing, you have a chance. And I just think at any moment people can start turning things around. You know just the fact for me, just the fact that you asked a question like that, I think is optimistic.

PM: Okay.

PS: You know, and also quite...I mean, I think it’s quite beautiful that you would ask me that question. It’s like, you’re what? 45 or something? I’m 68 years old. So I forget…I still feel young. I don’t feel like I’m an old…you know…like your grandma I’m talking to you. You know – we’re like two humans…not that there’s anything wrong with a grandma. I’m just saying that I don’t feel severed by that. Because what we’re doing is we’re communicating. And that’s what…that’s how change will be made. And uh…I don’t know, it’s a rough time. All I can say is you know, try to be happy and take care of your teeth.

PM: (laughs)

PS: Drink a lot of water. And take care of your teeth, because if you don’t, it’s really a drag when you get older. So keep your teeth clean.

PM: That’s so funny! My teeth are buggered. They all need to be replaced. I have not looked after my teeth. They are all messed up.

PS: Well, you know, just, this is what you do. My teeth were really messed up too. And what you do is just take the deep breathe. Go get them cleaned. See what you can do, and just try to do the best you can with them, because they’re really going to bug you when you get older…I know I’m like…I really spend a lot of time talking to people about their teeth because my generation had the worst teeth and the worst dental care. And when you get older, it’s a pain in the ass.

Because people think ‘it’s just your teeth’ and so they’re worried about their kidneys or their liver. But your teeth are really important. So, take care of your teeth as best you can. Drink a lot of water. And um, you know, cultivate your mind. You obviously have a good mind. And just, you know...but try to be happy. Because the world is fucked up.

PM: (laughs)

PS: There’s no…I can’t pretend, or say “oh, it’s not as bad as you think”. Yes dear, the world is fucked up.

PM: (laughs)

PS: And a lot of reasons it’s fucked up is my country. But with all that, as an individual…I tell my kids too…you know…you like think of yourself like a captain, and you’ve got this little boat. And sometimes the weather’s good, and you’re just sailing, and sometimes big storms hit, and you know, you’re in a stormy sea, but just ride it out, ride it out. Because it’s good to be alive.

PM: It is. And it’s even better, having spent half an hour talking to you. I’m beaming with happiness Patti. Thank you so much.

PS: Well, thank you. It was really nice to talking to you. And take care of yourself, okay.

PM: Thank you Patti. I hope you have an excellent sleep, and wake rejuvenated. I send all my love to you.

PS: Thank you. Bye.

PM: Cheers.

This interview was first published on Salon.com

© PETER MACHEN 2017