The Wars that Wage

The Wars that Wage

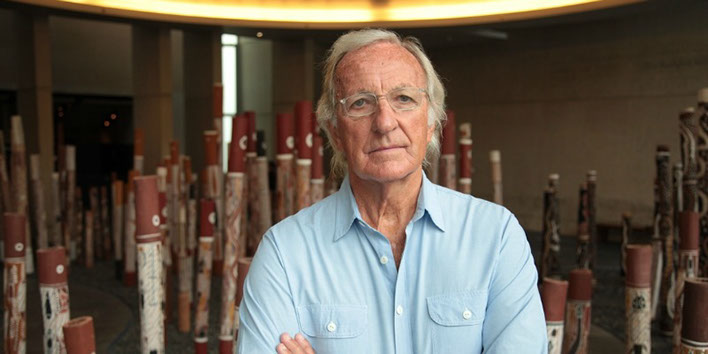

Peter Machen speaks to John Pilger

John Pilger is a war correspondent in the broadest sense. Since the early ’60s he has been covering the wars waged against humanity around the planet.

These wars have been waged with napalm and firebombs, scud missiles and AK47s, chemical warfare and child soldiers. But the horrors of what we consider to be “conventional” warfare is equally matched by the horrors executed in economic terms by Western powers and multinational corporations – the decimation of national economies in the name of structural adjustment and the human suffering and loss of life that results, the systematic stripping of the physical and human resources of the third world, the economic totalitarianism that has so often been made a condition of the “independence” of third world countries from their colonial masters.

Our minds and heart recoil when we think of the Jewish holocaust or the holocaust of the slave trade, and yet we manage to live in a global society which manages to absorb – without a single front page headline – a holocaust of nearly ten million children dying every year from malnutrition, as Pilger points out below.

Through Pilger’s films and writings – which spans more than four decades, and includes more than 50 documentaries and countless newspaper and magazine features, many of which have been collected in his books – the confluence of all this violence is revealed. The war promulgated by Margaret Thatcher against British miners in the ’80s is seen to be part of the same systematic onslaught of the powerful against the powerless that includes the American invasion of Iraq, the battles of the landless peoples in South Africa and around the world, and a global military complex that is largely controlled and supplied by the West, with supercapitalist profit as its guiding principle, what Pilger calls the economic 'supercult' of neoliberalism.

In a sobering interview, I chatted to Pilger about these seemingly endless wars, the rising world consciousness that exists in the face of this aggression, and about how we can respond personally to an increasingly unequal world.

Peter Machen: In the introduction to Hidden Agendas (1998), you wrote about the beacons of hope which shine light onto the imperial darkness: the heroic individuals and organisations – ordinary people all over the world – who are fighting for all of us to maintain our humanity.

I wrote a short column about the same time as your book was published, with the same theme and expressing a similar sentiment of hope for the future. But a decade later it seems that even as activists around the world have become more determined, and western citizens more aware of the vast inequalities and the grossness and emptiness of a system that exists in their name, the mechanism of state-sponsored global capital has become ever more vigorous, more controlling, more violent. Do you think that we, the people, can win this war?

John Pilger: It’s around a decade since you wrote that column, and that’s a very short time. Look at the previous decade. Would you have predicted the collapse of apartheid in your own country? Perhaps you did predict it. Many didn’t. That said, we have to be patient with history. Think how long it took to win the war against slavery and for democratic rights for women. Yes, these days are often dark times -- the regime in Washington is dangerous and rampant -- and yet I have never known a time when people are more aware, especially of the often subtle ways great power touches their lives. It’s this consciousness that will force its way past the militarists and those who promote supercults in the name of rational economics. The most recent, singular achievement of the last decade is that the largest nation in the Middle East, Iran, has not been attacked by the United States. Why? Because of popular opposition around the world and in the United States. Taking your broad question, I don’t know if “people can win this war”, but I do know that people are never still, and that there is always “a seed beneath the snow”. That’s the lesson of history.

PM: The strength of the phrase “they are few, we are many” seems diminished when it is “they” who have most of the weapons of war, and who control virtually everything. I am starting to feel, like so many others, helpless and often depressed (a thousand page of Pilger didn’t make me feel better, but it made me angrier). Are my notes of defeatism simply part of “their” plan?

JP: Yes, your sense of “defeatism”, as you put it, is part of “their” plan. Persuading people that they can do nothing to change their lives, to bring decency and justice into human affairs and that they are isolated -- in other words, persuading them to believe that history has ended -- is a constant theme of today’s media. Understanding this is the first step to overcoming it. And people who take action to overcome it have little time to be “depressed”.

PM: I studied economics for too many years for my own mental health. And the core of it, from high school to honours level, was devoted to justifying neoliberalism – in almost exclusively theoretical terms and ignoring most of history. A tiny proportion of seven years of study was devoted to alternative economic models, models that often make more intuitive sense and bear more relation to reality. Do you think that the academies bear much blame for the state of the world which you depict in your writing and filmmaking?

JP: I do believe the academies bear much blame for instilling into students that there is only one way to organise our economic lives. Disseminating the propaganda of so-called neo-liberalism, an anti-human super-cult that makes no sense except for those who make huge profits from its imposition, has made a mockery of so much scholarship, with its corporate training disguised as education.

PM: Like an increasing proportion of consumers, I try to use my economic power responsibly – boycotting multinationals wherever possible, trying to buy products that have been produced locally and non-exploitatively, helping those around me whenever I can. While this means that my own complicity in an oppressive system is reduced (although I still drive a car, I still pay my water-bill and the payments on my house to multinational corporations), I can’t help but feel as if I’m farting against thunder. At the same time we could close down irresponsible corporates such as McDonalds and Nike tomorrow simply by not buying their products. I understand also that having such economic choices is usually a middle-class luxury. Do you think that such actions are ultimately of much use?

JP: A suggestion -- try not to describe yourself as a “consumer”. That’s the jargon of the propaganda we’re discussing. Yes, some boycotts are ineffective; but many are not. For example, the boycott of South African goods during the latter years of apartheid contributed to bringing down the regime. Multinationals were driven out of Burma because of boycotts in the United States. In some of its Indonesian factories, Nike was forced to accede to workers’ demands for improved conditions because of the threat of boycotts. However, boycotts only work when, as in South Africa, they are part of a wider political action

PM: Western aggression is often justified as defending a threat to “our way of life”. Of course, the great irony is that it is governments and capital which have consistently been the great threat to our ways of life. The beginning of my own sense of activism was founded not only in the fate of others, but also in the intrusion of the state and capital into my own middle-class life, both during apartheid and after its apparent demise.

Constant surveillance, the destruction of public space, the control of the banking system, the loss of freedoms of assembly, the enormous cost of private healthcare, the colonisation of our physical and emotional life by marketing: these things drive me mad at times. The terrible things that happen to far less fortunate others drive me to the edge of sanity. And yet so many middle-class people seem fine with it all.

How do you think people manage to absorb all of this stuff and still feel fine? And how you cope on an emotional level with your super-awareness of the ongoing atrocities on the planet? Do you ever get depressed? Is that a stupid question?

JP: Yes, I sometimes get depressed. I’ve noticed the word “depressed” keeps cropping up in your questions. The kind of despair you’re alluding to is blown away by bold, direct action.

PM: Do you think that in political terms psychopaths tend to rise to the top, or is it the process of rising to the top that induces psychopathy? I use this word, because I can’t think of another word to describe the minds that can allow countless thousands to die in the pursuit of economic and political power. How did we allow them to get to this point? I think also of Robert Mugabe who gave his people health and education but is now taking everything away.

JP: No, I don’t believe psychopaths necessarily rise to the top, but an unaccountable system almost guarantees that sociopaths do - the list is long. That’s why totalitarianism is defeated and democracy is only true when everything is accountable.

PM: Have you seen the film Zeitgeist which presents a plan for world domination by big business, something that has already been substantially achieved? Do you think that the endless expansion of empire and multinationals is part of a broad plan, or is it just a relentless tendency, the mechanisms of history playing themselves out?

JP: I don’t know what you mean by “the mechanisms of history playing themselves out”. This suggests that everything is pre-ordered, almost pre-ordained, and that we might as well retire to the nearest monastery. The opposite is true, in my view. I also believe that it’s clear to most people -- particularly those who are at the heel-end of great power’s boot -- that decent humanity has nothing in common with a system that has caused the greatest divisions in our history. There are different names for this system, and different versions on display, but basically it’s the same thing

PM: Do you think, given the available resources and technology, that it is possible to provide for the needs and comfort of all the earth’s people?

JP: Yes, I do. The evidence is abundant. Indeed, it’s ridiculous, given the resources and technology available, that 26 000 children die every day from the effects of poverty. No child should die for want of basic nourishment. Nothing is more absurd.

PM: One thing that I simply fail to understand is why these people at the top need so much power, such an infinity of wealth. What do you think it does for them? Do you think that they are people like you and me who have simply sacrificed their souls for lucre? Because it almost seems darker than that, it almost feels – and I am being allegorical – that we are being colonised by another species, one that cares nothing for the profoundly beautiful experience of being human.

JP: I agree with you. I don’t understand why certain people “at the top” need so much wealth. But “need” is not a word in their vocabulary, because they never have to use it. Their affliction is known as “greed” – and the greedier they are, the more they believe it’s their divine right to have more. They must be very tedious company.

PM: Finally, I know that you’re a reporter, not an adviser to the world, but what can ordinary people, people reading this interview, for example, do to fight this war against inequality? How can they make a difference?

JP: First of all, people have to want to “fight this war against inequality”. That’s the first step. When they take that first step, and like people all over the world who have fought, often literally for their freedom, they won’t need to be told what to do next.

PM: John, thank you so much for this interview, and also for your lack of moral relativism, your insistence that there are unarguable truths to be found in this world.

© PETER MACHEN 2017