The Edge of Darkness

The Edge of Darkness

Peter Machen speaks to internationally acclaimed photographer Roger Ballen, whose exhibition Boarding House is currently on show at the Durban Art Gallery

One of the world's most acclaimed photographers, Roger Ballen has been working in South Africa since the late 1970s, documenting specific margins of the country, from the idiosyncratic landscapes of its small towns and their inhabitants to the dilapidated surreality of his latest exhibition entitled Boarding House.

Over the course of four decades and numerous books and shows, Ballen, who was born and grew up in America, and who still talks in a clipped American accent, has evolved a style that is entirely his own, and whose references such as they exist, are more reminiscent of primeval consciousness than they are reflective of the ebbs and flows of the 21st century art world.

And while the lineage of his concerns descends both conceptually and aesthetically from the dadaists and surrealists of the '20s and '30s, it is in the evolution of his own body of work that is the most profound influence on his photography, as his work has shifted ever closer to abstraction while never abandoning technical precision. The blur, such as it exists in his work, is only ever conceptual.

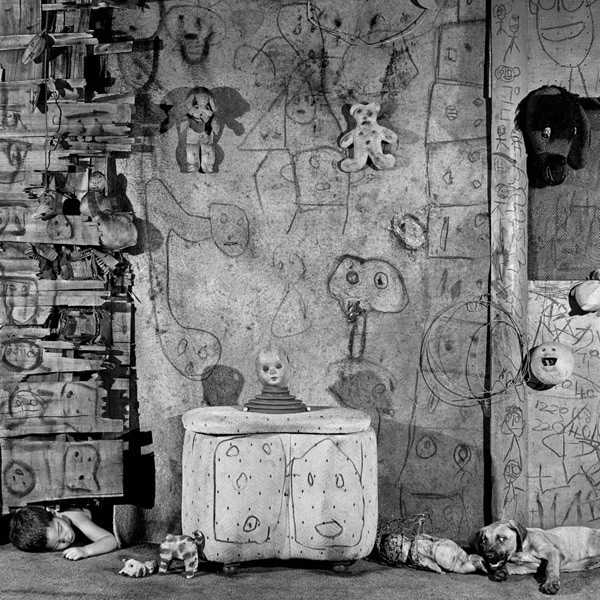

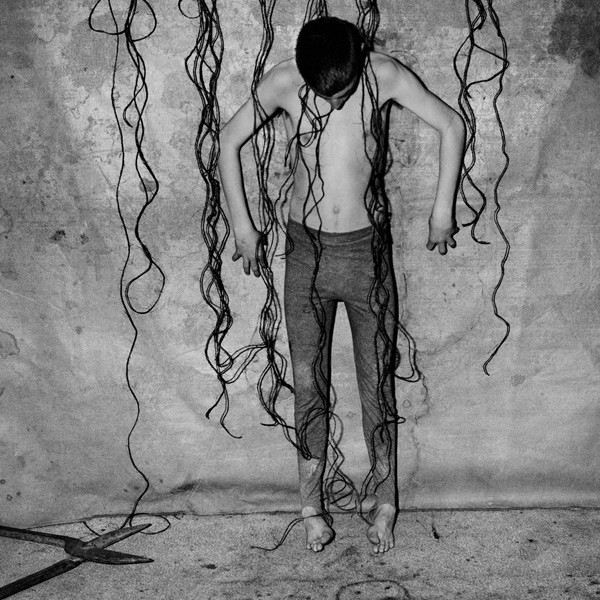

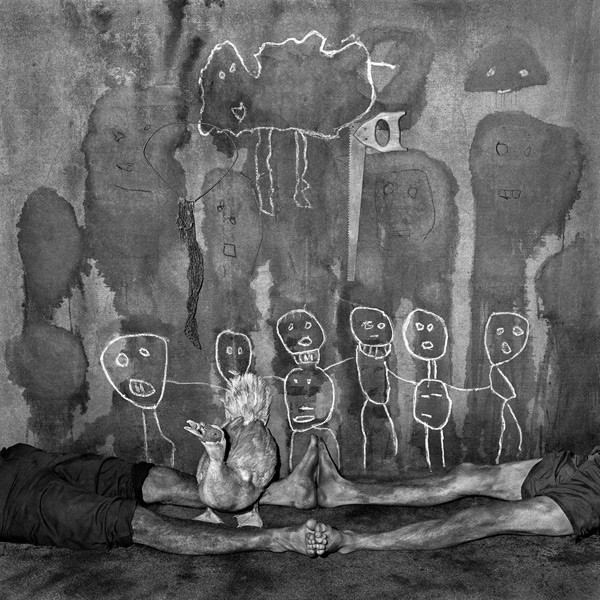

The endless collage of primitivism and surrealism that constitutes Boarding House, currently on show at the Durban Art Gallery, is both a microscopic zoom into the details that already existed in Ballen's early work, and a telescopic pan across the vastness and darkness of human consciousness. Where once he chronicled the exterior strangeness of South Africa's dorps, he now increasingly moves into an into an irrational, primeval interior space where figurativeness itself dissolves, along with words and what we conventionally refer to as meaning.

These chronicles of the unconscious have, for the last five years, taken place in a space that Ballen refers to as 'the boarding house'. While the boarding house is a physical space just outside of Johannesburg that is in many ways just as extreme as it is depicted, it is far more dominantly a psychological space. Says Ballen, quoted in curator David Travis' introduction to the catalogue for the show, “During the process of creating Boarding House I broke through or into parts of my mind that I never knew existed. It was quite enthralling to find and be in this place. It is difficult to explain this place, except that I think it exists in some way or another in most people's minds.”

There seems to be some truth to this suggestion that he is delving into a collective unconscious. For while the markings in Ballen's images may faintly echo cave paintings, they are also part of a universal language that is both contemporary and probably as old as human marking. Even in Durban, if you look beyond the façades of our mall culture, you might recognise the markings in Ballen's images. For they are similar to markings on freeway balustrades, pavements, pedestrian bridges and ghettoised walls, spaces occupied by street children, the destitute and the untethered. It bears pointing out that these marking are generally very different to street art (although not dissimilar to outsider art). They exist without the stylisation that tends to defines artistic production. They are products of the id more than of the ego.

Over the years, Ballen has faced a fairly substantial barrage of criticism, criticisms whose concerns have ranged from exploitation of South African subjects by an American photographer to the extent to which his images have been constructed, as if construction somehow robs them of authenticity. But all those who discuss the various ways in which Ballen's photographs are or are not constructed, or the relationship he has with the unseen collaborators and increasingly occasional human subjects, are missing at least one essential point. And that is that the work produced for Boarding House and his numerous other exhibitions are the work of Roger Ballen. It's a strange thing to say but we seem to automatically forget – perpetually – that photographers make photographs as surely as painters make painting. That every photograph ever taken is actually constructed, whether over days or weeks – as with an advertising image – or in one 500th of a second, as might be the case with the work of a war correspondent.

But more than that, there is often the sense that, in constructing his images – and also in not acknowledging a discreet separation between that which is found and that which is added – Ballen is somehow guilty of a cardinal sin. “This is one of the biggest problems we face in photography, this issue,” says Ballen, when I bring it up with him. “The most immediate question and frequent question is 'is this a real place?'. They can't accept that what's on the wall is what they have to deal with.”

For Ballen these predisposed ways of looking at a photograph is a huge hurdle in his own work and in photography in gaeneral. “And this comes up over and over and over again”. His response to the questions of 'is this real?' goes for the metaphysical jugular. “Well, if one closes one's eyes and thinks about how one's mind works, it goes between memory, between imagination, between feeling the body. We actually have multiple levels of consciousness all the time. So there isn't anything real out there. It's always a mixture of this and that.”

“And I think”, he continues, “if one goes back to these pictures, it actually brings up that issue in all sorts of ways. So you're right, there's a predisposed prejudice in photography. But, I think, you know, that people just have to look at the pictures for what they are, accept them for what they are. It's a reflection of ignorance rather than anything else, that predisposition that's out there. As a photographer you have to deal with it. You can't pretend it doesn't exist.”

He points to a picture in another room in the gallery taken by a leading South African artist. “For example, that photograph doesn't mean anything to anyone. So you've got to read about it [in the notes underneath it]. The differences between that and something here [in the Boarding House exhibition] is that these things strike you right in the stomach, and you can't get them out of you. You don't have to read about it.”

“And the difference between someone who really understands photography and that kind of work – which you see a lot of in today's world, you see a lot of artists using their cameras but they don't actually understand photography – is that everything you see here has been transformed, ultimately, photographically. If you have to write about it in order to have impact on people's mind - if you go that far - then you lose it.”

He continues, “Look at the cloud. Look at the tree. Those are the things that are all around you, the things that you need to inspire you and to give you the right direction. And that's what you should be doing: through your life experience, finding those things that will give you a way forward.”

© PETER MACHEN 2017