City of Grace and Freedom

Peter Machen found himself bewitched by Maputo's beautifully broken elegance

Socialism stills walks the streets of Maputo. Any communist or socialist with any degree of fame (or notoriety, depending on the fickleness of history) has a street named after them. You can walk downtown along Avenida Karl Marx or Avenida Vladimir Lenine. Mao Tse-tung, Ho Chi Minh and Albert Luthuli all have avenues named in their honour. And while the potholes and peeling paint that decorate the city might stand as a metaphor for the current state of socialism, the beauty of being in Maputo – the people, the buildings, the colour of the light – continues to offer hope for an alternative model of social and economic reality in Africa.

Maputo is an extremely poor city in an extremely poor country. Like South Africa, there is massive unemployment. Prices are higher and salaries are lower. Nearly everything is imported, refuse removal is minimal and the police are a law unto themselves.

Yet somehow everything kind of works. There are far fewer beggars on the streets than in any South African city. You can sit at a pavement cafe drinking an excellent espresso and a delicately delicious pastry and not feel compelled to think you're in Europe. This is Africa, pure, simple, beautiful, and without pretensions.

The Coca-Cola signs are coming, sure, and there are cheesy billboards advertising the promise of connectivity in the form of cellphones – and, in a streak of historic irony, some of the new construction is surrounded by hoardings painted with the ANC colours.

But the rabid consumerism that has come to characterise post-apartheid South Africa is largely absent from Maputo. Walking through the sprawling Xipamanini market in the poorer end of the city, or the more upmarket Mercardo Municipal downtown, it seems that the sellers outnumber the buyers a hundred to one. Only in the very specifically upper middle-class Supermercado does commerce begin to resemble anything like South Africa.

And, apart from the curio-sellers who line the roads where the hotels are located, bargaining will get you nowhere. Even in the shops, prices are standardised in the same way as they are on the streets of South Africa, with hundreds of hawkers selling a range of identical goods at the same price.

And the people are almost painfully honest. Often I would leave vendors with 500 meticas change (about 20 cents) and without fail, they would run after me clutching the coin to return it.

Service in Maputo is impeccable (tips are appreciated but not expected) and food arrives at ones table remarkably quickly since even the grilled sandwich machines run on gas. You are discouraged from drinking the tap water but the locals do and with my southern African stomach I didn't have a problem. We ate a meal at a fantastic Ethiopian restaurant at the Faire Populer, and although there were no functional taps in the bathroom, our waitress brought a basin and a jug of water that she poured over our hands before we ate.

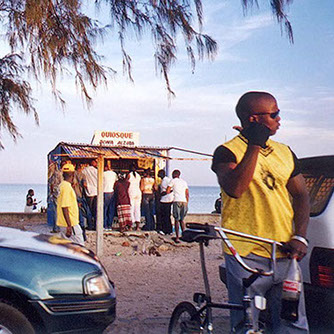

One of the defining characteristics of Maputo is its vibrant pavement culture. From the cigarette vendors that dot the streets until late into the night to the pastelerias (bakeries) and coffee shops, the streets are alive with an ease and elegance that we are far from acquiring.

Likewise, some liquor stores are open until midnight and it's acceptable to drink in public. And while there is a strong drinking culture, it's not a culture of getting wasted in the great South African tradition. Every morning there were people in the coffee shops still going from the night before but looking inexplicably fresh.

The people are beautiful and friendly. If the buildings are haunted by war, the people, it seems, are not. While poverty is everywhere, there is little sense of the brutalisation that continues to remain so visible in South Africa. There is a sense of life simply being lived. And this is not the condescending view of a white middle-class tourist. I spoke to many Mozambicans who lived in South Africa for one reason or another (usually jobs and rands, sometimes family) and without exception they were all glad to be back in Maputo for Christmas because life was more real here. The paradox, of course, is that they need to return to South Africa to work. The big social and economic question is whether it is possible to conjoin the freedom of Maputo with any kind of real capitalism.

The architecture is truly lovely, despite (and because of) the poverty and dilapidation of war - a melting pot of Brazilian modernism, old-school colonialism and African style. The most striking thing is the individuality of every building, every street, every detail. A single medium-rise block of flats might have 20 different styles of burglar guards for example. Looking out from a rooftop across the cityscape, a criss-cross of shapes and patterns emerges that is inspiring in its acknowledgment of difference and commonality. And if the banality of South African postmodernism is starting to spread in the form of the office parks that are popping up in the business district downtown, such grossnesses will hopefully be restrained by the ghosts of socialism that continue to linger amid the encroaching billboards.

Despite the dilapidation, the cracks in the buildings, the potholes and the questions around its economic future, Maputo has a lot to teach South Africa. There is a freedom and fluidity here that barely exists in South Africa. And racial identity seems far less relevant despite a strong history of colonialism.

Maputo is a city out of time, almost forgotten by the ravages and progress of history. But life is lived here with a broadly human grace that one day we might all acquire. You might just have to slow down a little to see it.

This story was first published in The Independent on Saturday

© PETER MACHEN 2017