Occupational Therapy

Occupational Therapy

William Kentridge is South Africa's most well-known artistic export. He also remains most famous for his short animated films. I spoke to him about these shorts, which are now collected as 9 Films and are prefaced by a more complex animation called Journey to the Moon, which incorporates non-drawn material.

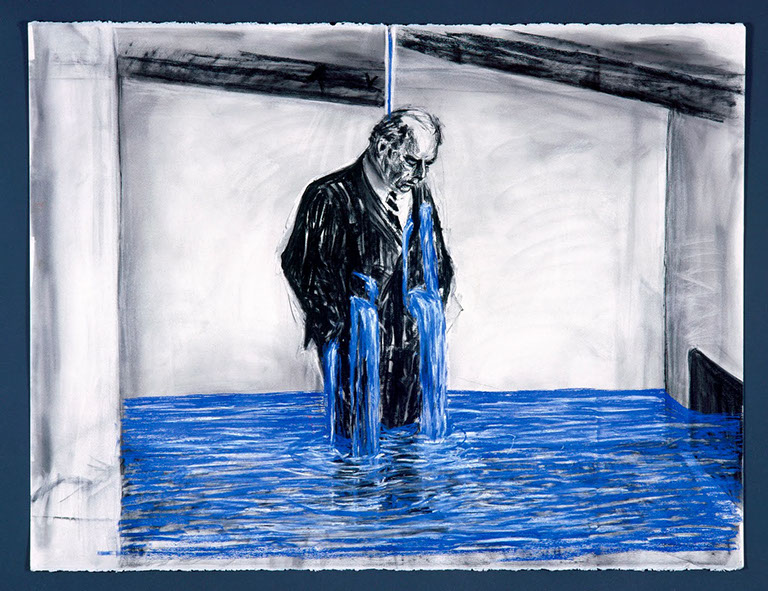

William Kentridge's primary medium is charcoal on paper. Unlike most animators, he does not use thousands of different cels but instead draws onto a piece of paper, takes a photograph or two of the image, erases the element he is animating, redraws the next frame and takes another photograph. And so on, until eventually there are thousands of photographs that constitute a film. But each erasure is imperfect and so images leave behind traces of their history.

This is one of the most primitive forms of cinema, and Kentridge is its master. It is an extremely laborious process, one that the artist himself admits is "perilously close to occupational therapy". A week's worth of drawings will give him 40 seconds of footage. But sheer volume of time aside, it is a remarkable, efficient and compact process compared to the extravaganza involved in making normal cinema. Kentridge might use 20 pieces of paper to make an eight-minute film, as opposed to the thousands of individually drawn frames that are used for a conventional cartoon.

This erasure technique is used by Kentridge in a series of short films he made between 1989 and now. In these films, which explore the world of mining magnate Soho Eckstein, Kentridge's alter ego Felix Teitlebaum and Mrs Eckstein, the woman who connects the two men to each other in the artificial landscape of early 1970s Johannesburg, the technique itself becomes a reflexive element of a society that is erasing the past.

When Kentridge first started using the technique, he had no idea that it would have such metaphoric significance or endurance.

In fact, he says that he viewed it more as a mistake that he could only do an imperfect erasure. And only after he'd completed several films did he understand that the erasure and the trace of the marks was part of the meaning of the films as well.

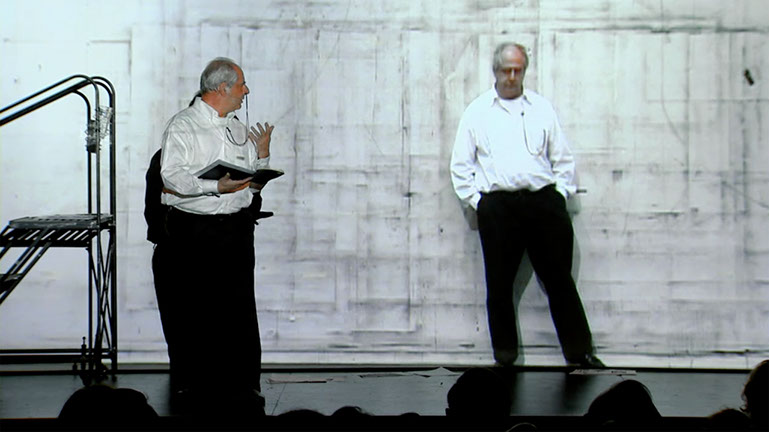

In Durban's City Hall on Friday, Kentridge will be showing the nine films, with the Sontonga Quartet performing the soundtrack. Partly a tribute to the early days of cinema, when silent movies were accompanied by live scored performances, Kentridge says that viewing the films on a large scale with live musicians is "a different experience".

"And it's a double vision - you see the film and below the screen you see the performers making the music. A lot of people who'd heard the music before very many times suddenly have said that they heard it in a very different way."

In the catalogue for his exhibition at Castela Di Rivoli, one of the writers refers to Adorno's assertion that after Auschwitz, it would be barbaric to write poetry. Likewise, Kentridge himself talks about the impossibility for himself personally of creating utopian landscapes in the manner of the expressionists. The lyrical and the poetic are seen as too great a luxury in such a broken landscape as Johannesburg's.

Yet, at the same time the poetic, Arcadian images Kentridge professes not to be able to draw without descending into kitsch are about loss - and, if not about loss, he acknowledges, at least about uncomplicated desire. Conversely, his short films, while they walk the line between hope and darkness, are also deeply lyrical and poetic in a far more 20th century manner, and contain an iridescent but deeply embedded set of desires.

But, says Kentridge, that's really something that a viewer would see more clearly than he ever would or could.

"I'm working on them frame by frame", he says, "sequence by sequence, in the hope that they'll add up to something coherent. If there is a smoothness or a lyricism in it, then that's great but that's not an aim or an objective. But I think the way they're structured and the way that they work from the inside out may have more to do with the way one would write a poem than the way one would write a paragraph of prose."

And in fact, the films feel like incredibly dense literary works, very short stories. The preface to the 9 Films, Journey to the Moon, is Kentridge's tribute to the pioneers of film. Combining "live" animation in his studio with charcoal animations and more experimental techniques, it is a very beautiful piece of cinema that explores the artistic process itself.

© PETER MACHEN 2017